May 21, 1956: Beach closed after black, white teens caught 'talking'

Delray Beach police offered vague explanations for closing a section of beach after finding a "tense group" of white and "Negro" teens talking to each other.

This happened during an era when African Americans were whittling away at the South's Jim Crow laws by suing one segregated place at a time. As federal courts upheld blacks' rights to access public businesses and facilities, local authorities were being pressured to find any excuse to keep the races apart. Yet, the authorities were often hardpressed to justify their actions because that could subject them to claims they violated federally guaranteed civil rights.

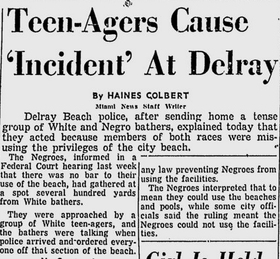

And so an unnamed Delray Beach police officer found himself pressured by Miami Daily News reporter Haines Colbert to explain why his chief closed a section of his city's beach the day before after noticing a group of white "bathers" talking with a group of "Negroes."

This must have been a jarring sight to the police because African Americans were not traditionally allowed on most Florida beaches. These particular teens were emboldened to come to the beach because a federal judge in Miami had the previous week dismissed a claim by local blacks that they had been denied use of the city's recreational facilities.

The judge dismissed the suit after city officials insisted "there was not, and never had been, any law preventing Negroes from using the facilities," the story said, adding, "The Negroes interpreted that to mean they could use the beaches and pools."

Well, maybe the ruling meant they could use the public swimming pool but coincidentally the city closed it indefinitely for "repairs" after the ruling.

The group of African American teens that decided to go to the beach gathered "several hundred yards from white bathers," the story said. A group of the white kids approached them "and the bathers were talking when police arrived and ordered everyone off that section of the beach," the story said.

An officer who took part in the action insisted the "Negroes" were not driven away because of their color.

"It looked as if there might be trouble," the officer said. As far as he knew, there was no reason the African American kids couldn't come back to the beach the following day.

The story is framed to make the reader wonder if the police closed the beach to chase off the black kids. But it doesn't detail what the groups were "talking" about or why the white kids approached the black teens.

The lead sentence states the police sent home a "tense group of White and Negro bathers" who were "misusing the privileges of the city beach."

Later, the story quotes the officer as saying there was no violence and "he did not know if there was any argument."

This happened during an era when African Americans were whittling away at the South's Jim Crow laws by suing one segregated place at a time. As federal courts upheld blacks' rights to access public businesses and facilities, local authorities were being pressured to find any excuse to keep the races apart. Yet, the authorities were often hardpressed to justify their actions because that could subject them to claims they violated federally guaranteed civil rights.

And so an unnamed Delray Beach police officer found himself pressured by Miami Daily News reporter Haines Colbert to explain why his chief closed a section of his city's beach the day before after noticing a group of white "bathers" talking with a group of "Negroes."

This must have been a jarring sight to the police because African Americans were not traditionally allowed on most Florida beaches. These particular teens were emboldened to come to the beach because a federal judge in Miami had the previous week dismissed a claim by local blacks that they had been denied use of the city's recreational facilities.

The judge dismissed the suit after city officials insisted "there was not, and never had been, any law preventing Negroes from using the facilities," the story said, adding, "The Negroes interpreted that to mean they could use the beaches and pools."

Well, maybe the ruling meant they could use the public swimming pool but coincidentally the city closed it indefinitely for "repairs" after the ruling.

The group of African American teens that decided to go to the beach gathered "several hundred yards from white bathers," the story said. A group of the white kids approached them "and the bathers were talking when police arrived and ordered everyone off that section of the beach," the story said.

An officer who took part in the action insisted the "Negroes" were not driven away because of their color.

"It looked as if there might be trouble," the officer said. As far as he knew, there was no reason the African American kids couldn't come back to the beach the following day.

The story is framed to make the reader wonder if the police closed the beach to chase off the black kids. But it doesn't detail what the groups were "talking" about or why the white kids approached the black teens.

The lead sentence states the police sent home a "tense group of White and Negro bathers" who were "misusing the privileges of the city beach."

Later, the story quotes the officer as saying there was no violence and "he did not know if there was any argument."

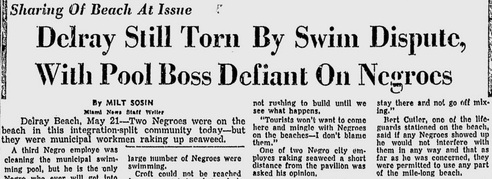

A follow-up story by another reporter in a later edition of the paper states that Police Chief R.C. Croft said he closed the beach to prevent any violence.

The story also said the city pool would be reopened the next day, but aquatic director Steve Forsythe vowed to close it again if "Negroes" showed up and swam -- even if closing the pool meant he would be fired.

Firing Forsythe "is a possibility that may well have to be considered," said City Manager William E. Lawson Jr.

Whites and blacks along the beach were asked their opinions of the controversy.

A white lady from Chicago said she would delay building a retirement home on the beach until she found out whether blacks would be allowed there. "Tourists won't want to come here and mingle with Negroes on the beaches--I don't blame them," she said.

A black city employee was raking seaweed on the beach when asked about the matter.

"We don't want to mix with the whites," he said. "All we want is a place to go bathing and swimming. We don't have a single place up here where we can go. If they would give us a little portion of the beach we would stay there and not go off mixing."

Lifeguard Bert Cutler said "if any Negroes showed up he would not interfere with them in any way and that as far as he was concerned, they were permitted to use any part of that mile-long beach."

Click here to read the stories in the Miami Daily News:

• Teen-Agers Cause Incident At Delray

• Delray Still Torn By Swim Dispute With Pool Boss Defiant On Negroes

The story also said the city pool would be reopened the next day, but aquatic director Steve Forsythe vowed to close it again if "Negroes" showed up and swam -- even if closing the pool meant he would be fired.

Firing Forsythe "is a possibility that may well have to be considered," said City Manager William E. Lawson Jr.

Whites and blacks along the beach were asked their opinions of the controversy.

A white lady from Chicago said she would delay building a retirement home on the beach until she found out whether blacks would be allowed there. "Tourists won't want to come here and mingle with Negroes on the beaches--I don't blame them," she said.

A black city employee was raking seaweed on the beach when asked about the matter.

"We don't want to mix with the whites," he said. "All we want is a place to go bathing and swimming. We don't have a single place up here where we can go. If they would give us a little portion of the beach we would stay there and not go off mixing."

Lifeguard Bert Cutler said "if any Negroes showed up he would not interfere with them in any way and that as far as he was concerned, they were permitted to use any part of that mile-long beach."

Click here to read the stories in the Miami Daily News:

• Teen-Agers Cause Incident At Delray

• Delray Still Torn By Swim Dispute With Pool Boss Defiant On Negroes